The study found that participants were likelier to exploit female-labelled and distrust male-labelled AI agents than their human counterparts, reflecting gender biases in human interactions. Notably, defection against humans was driven primarily by distrust (70.5%), whereas defection against AI agents was more influenced by exploitation motives (40.6%). These findings underscore the need to address gender biases in designing and regulating AI systems.

Related Work

Past research has explored factors influencing human cooperation, including selfishness, in-group favoritism, and cultural attitudes toward new technologies.

Studies have shown that people cooperate less with AI agents than humans, often exploiting AI for personal gain. Human-like features, such as gender, have been shown to influence interactions, with gender biases extending to human-AI relations.

The prisoner's dilemma game has been widely used to study cooperation and defection, with gender biases observed in human-human interactions. Still, little is known about how AI's assigned gender affects cooperation.

Prisoner's Dilemma Experiment

The experimental design involved a series of online Prisoner's Dilemma games to study human decision-making in cooperative and competitive contexts. Participants (402 total, including 223 females and 179 males) were recruited from the United Kingdom (UK) via Prolific in July 2023 and anonymized to ensure privacy.

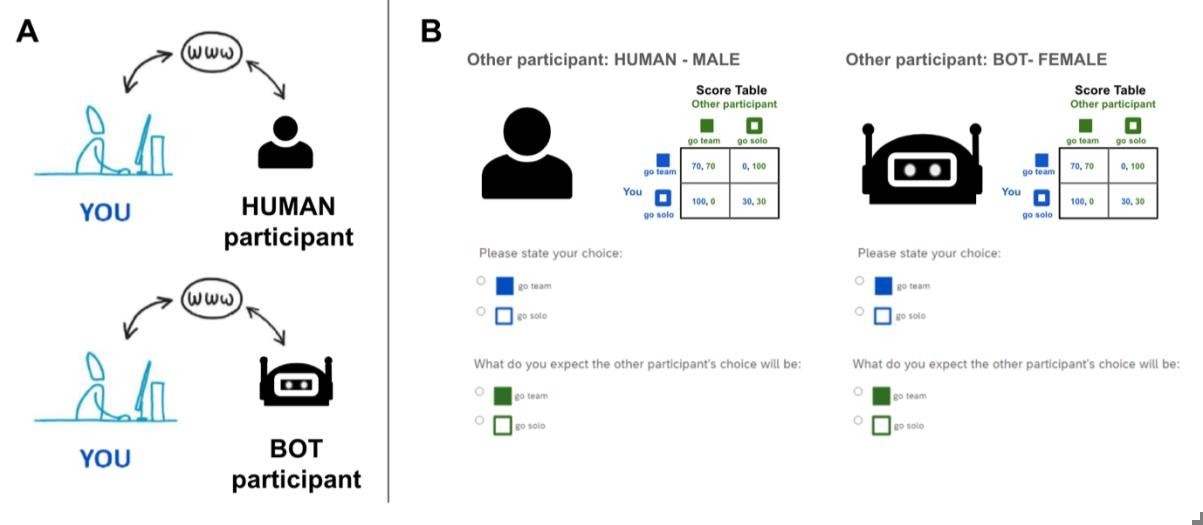

Prisoner’s Dilemma game in experimental trials. A. Participants are informed whether their partner is a human or an AI bot and the partner’s gender in the Prisoner’s Dilemma game. B. Examples of the experimental trial screen for two treatments. Participants are shown a label as an icon and text describing the partner with whom they are playing. They are also shown the Prisoner’s Dilemma game score table as a reminder. Participants are required to enter their choice of how to play against their partner (“go team” or “go solo”) and their expectations of their partner’s choice.

Participants in the experiment played ten rounds of the Prisoner's Dilemma game using both AI-controlled and human partners. The game involved choosing whether to cooperate ("go team") or defect ("go solo") based on points that translated into monetary rewards. After each round, participants predicted their partner's choice, and partner labels (human or AI) and gender identification were randomly assigned.

The analysis focused on participants' decisions and their predictions of partners' actions, aiming to identify behavioral motives like cooperation, exploitation, defection, or irrational cooperation.

Monte Carlo simulations were used to benchmark the observed behaviors against random chance, ensuring that causal relationships between decisions and predictions could be statistically validated. Additionally, participants completed a post-experiment survey to assess their attitudes toward AI, and a principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted to measure the overall AI attitude of each participant.

Logistic regression analysis further examined the effects of participant and partner gender, AI attitudes, and their interactions on cooperation tendencies.

Lastly, baseline calculations were used to examine the impacts of gender interaction after controlling for the participant's and their partner's gender.

Analysts calculated the odds of cooperative behavior for each gender pair and compared them with baseline expectations. The odds and log odds ratios were computed to assess whether observed cooperation rates differed from the baseline.

Binomial tests were then conducted for each gender interaction group to evaluate the statistical significance of deviations from the expected cooperation rates.

Gender Differences in Cooperation

In a study comparing cooperation between AI agents and human partners, participants cooperated slightly more with humans (52%) than with AI agents (49%), but this difference was not statistically significant. However, when participants defected, the reasons behind their decisions varied.

Defection against humans was mostly driven by a lack of trust in their partner (70.5%). In comparison, defection against AI agents had a more significant proportion of participants willing to exploit the AI (40.6%) compared to humans (29.5%). These statistically significant differences indicate that trust and exploitation motives differ between human and AI interactions.

Whether the partner was AI or human, participants demonstrated greater collaboration with females than males. The collaboration rate was 39.7% for male and 58.6% for female players.

This pattern was consistent across human-human and human-AI interactions, with participants defecting more against male partners due to a lack of trust. However, exploitation was notably higher for female-labelled AI agents than for female human partners. When cooperating with female partners, there was a higher tendency to exploit them for personal gain.

These trends were confirmed by Monte Carlo simulations, which showed significant deviations from random behavior, emphasizing that participants' actions were influenced by their perceptions of their partner's gender. Statistical tests also confirmed that male participants were more likely to exploit AI agents compared to female participants.

Gender also influenced the participants' own cooperation tendencies.

Female participants tended to be more cooperative than male participants, with cooperation rates of 53.9% for females compared to 49.2% for males when interacting with human partners.

Males were more likely to exploit their partners, especially when interacting with AI partners.

When examining interactions between genders, female participants exhibited stronger cooperation with female partners, a trend that was weaker when interacting with male partners. This female-female cooperation tendency, or homophily, was significant in both human-human and human-AI interactions, though slightly weaker with AI agents. These gender dynamics were especially noticeable in human-human interactions and somewhat weaker but still significant in AI interactions.

Conclusion

To sum up, the study showed that assigning human-like gender to AI agents increased cooperation, though exploitation motives were more prevalent with AI than with humans. It confirmed that gender biases in human-human interactions extended to human-AI interactions, with females being treated more cooperatively than males. Female participants also exhibited homophily, cooperating more with females than males.

The study highlighted the need to address biases in AI design to foster trust and fairness in human-AI interactions. The findings emphasize that while gendered AI may encourage cooperation, it can also reinforce undesirable gender stereotypes and behaviors observed in human interactions.

*Important notice: arXiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as definitive, used to guide development decisions, or treated as established information in the field of artificial intelligence research.

*Important notice: arXiv publishes preliminary scientific reports that are not peer-reviewed and, therefore, should not be regarded as definitive, used to guide development decisions, or treated as established information in the field of artificial intelligence research.

Journal reference:

- Preliminary scientific report.

Bazazi, S., et al. (2024). AI’s assigned gender affects human-AI cooperation. ArXiv. DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2412.05214, https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.05214